Eminent Scientist André Isaacs Makes Chemistry Click in the Classroom and on TikTok

If you don't know chemist André Isaacs from TikTok, you should! Whether donning a Bridgerton-inspired gown or dancing with students in a rainbow lab coat, Isaacs (@drdre4000) regularly produces viral videos that showcase his love for chemistry.

He first felt drawn to the discipline as a student at St. George's College high school in Kingston, Jamaica. At the time, there was only one problem: chemistry didn’t quite click for him. He easily grasped math and physics, but chemistry required more effort. For extra help, he attended an adult continuing education Introduction to Chemistry class taught by his own uncle. Suddenly, chemistry became more relatable. His uncle regularly used helpful analogies, like comparing a strong chemical bond to the connection between a happy couple.

Isaacs began excelling in his chemistry courses. He went on to earn a scholarship to the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he majored in chemistry. He then completed a PhD in chemistry with a focus on synthetic chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania and a postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley. Today, Isaacs is an associate professor of chemistry at his undergraduate alma mater. He also serves on the executive committee for the ACS Division of Organic Chemistry and is one of C&EN’s 2022 Trailblazers.

Isaacs is an expert in using click chemistry to develop new methods for more efficiently synthesizing nitrogen heterocycles. But as he sees it, his most important achievement is making chemistry more accessible to students—both in the classroom and through his massive social media presence.

“I think people are drawn to my content because of the intersectional identities that I hold within myself,” he says, “and also because of the joy I show when doing chemistry with my students.”

Attendees of the ACS Spring 2024 meeting in New Orleans will learn more about Isaacs’s career and outreach when he delivers the Eminent Scientist Lecture on Monday, March 18, at 2:30 p.m. in Great Hall B/C of the Morial Convention Center. We spoke with Isaacs to get a sneak peek into his fascinating journey.

As an undergraduate, did you know immediately that you wanted to pursue a career in chemistry?

No, I felt torn. I loved chemistry, but I was really strong in math. I had some amazing chemistry educators in my first year that sealed the deal for me. Much like my uncle, my organic chemistry professor really made science come to life. We sometimes watched movie clips, for example, that showed how chemistry can be misrepresented in popular culture. I remember one clip that pictured scientists using mass spectrometry to determine the structure of a molecule. It was really funny because the instrument doesn’t actually give you that data.

My organic chemistry teacher was also very patient and extremely available for students. You could tell that he cared a lot. I could see myself having that same level of enthusiasm for chemistry and teaching. Once I took that class, there was just no going back. I never took another math course.

How has your education influenced your own approach to teaching chemistry?

I grew up in a heavily religious country, so my uncle often drew analogies between chemistry and religion. I try to think about what else we can connect science to today that would make students from diverse populations feel as if science relates to them.

Right now, students use social media so much, so I find myself on it too just to learn their vocabulary. It goes a long way toward making them feel that I appreciate them as a person enough to engage with them using their language.

In the classroom, I also try to use the music that they are listening to, and the trendy dance moves they like to learn, and turn those dances into learning about chemistry. We might, for example, pretend to be molecules and atoms and do a coordinated dance that acts out the mechanism of a reaction.

I also make sure that students are exposed to scientists from diverse backgrounds. I introduce them to African American scientists, for example, by having them watch videos or read about famous chemists like Alice Ball and Alma Levant Hayden. I’m trying to find ways to make sure that every population sees themselves in the science they learn.

Your academic research has spanned many different disciplines within chemistry. As a graduate student, you worked on synthesizing compounds that could inhibit a signaling pathway used by cancer cells to proliferate. As a postdoc, you switched to the field of total synthesis, where the goal is to synthesize complex molecules found in nature from simple starting materials. How did you settle on your current field of methods development?

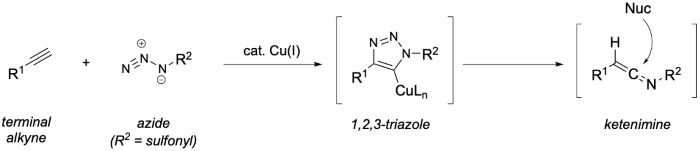

The goal of methods development is to find better ways to synthesize molecules that synthetic chemists commonly use to build even larger molecules. In my group, we use click chemistry to make triazoles. Triazoles are a type of nitrogen heterocycle—ring molecules that include at least one nitrogen atom. We then break down those triazoles and rebuild them into a range of different nitrogen heterocycles that can be used for synthesizing a range of more complex compounds used in many industries, from agriculture to medicine.

I designed this particular research program because the work is accessible for undergraduates in my lab. Click chemistry means working with reactions that are easy to set up and produce very efficient transformations. Students can do this well without having to learn very complicated setups.

You often publish with undergraduate coauthors. How important are undergraduates to your research program?

The undergraduates are everything to my research program. Our goal is to make significant contributions to the field of chemistry, of course. But my main goal is undergraduate training. We work together side by side. As a result, I have a large number of students who go on to chemistry careers in academia or the pharmaceutical industry. My favorite part of my job is hearing from former students who tell me that their time here prepared them well for their professions. And I love updating my website every time a former student gets a new job.

You also take your teaching onto social media. When did you start posting pictures and videos to Instagram and TikTok?

I started developing my social media platforms during the pandemic. Initially, it was a way for me to cope as an extrovert stuck at home. Then, once I went back to lab later that year and posted a video of me in my rainbow lab coat, I recognized that my platform could actually have a productive use. A lot of students and others were commenting on my video saying, “I didn’t know scientists could have fun like this!” and “Your rainbow lab coat means so much to me as a queer person in science.” I recognized at that point that I now had a platform that I could use to showcase joy in science but also to remind those who oftentimes feel as if they don’t belong in science that they do.

I’ve now posted hundreds of photos and videos. The videos often include me alongside my students showing off our dance moves in the lab. Or sometimes I record myself dancing or demonstrating an especially intriguing chemistry reaction. In one of my favorite videos, I use some fun chemical reactions to make it look like I am quickly turning water into wine, wine into milk, and then milk into beer. I also really love our graduation videos that celebrate students transitioning from the lab out into the professional world.

Why is it so critical to draw a more diverse group of students to chemistry? What is at stake?

What is at stake is chemistry itself. If we examine the mishaps that we have had in science, a lot of it is because we don’t have a diverse enough pool of scientists to think about areas that have been ignored. It’s really important in science to have all voices at the table so we can think about new solutions to the questions that we ask but also to think about new questions to ask to better society.

Also, for our society to have faith in scientists, people need to feel that they have representatives within science. If you don’t see scientists who you feel are advocating for you, then it is hard to have faith in what scientists do.

Finally, the data shows that the most cited scientific articles are the ones that have the most diverse coauthorships. The fact is that the best work is coming out from a pool of diverse scientists.

I spend a lot of time traveling to universities across the country to speak about how to retain students from diverse populations within chemistry.

Do you have any advice for undergraduates who are just beginning their chemistry career paths?

I think back to myself as a young student. I was interested in becoming a chemist, but I also liked fashion and tennis. It’s really hard to follow your dreams if you don’t allow yourself to do the things that really interest you. There is an amount of vulnerability that comes with that. Be vulnerable with yourself. But find and lean on the people who are willing to support you. It is so important.