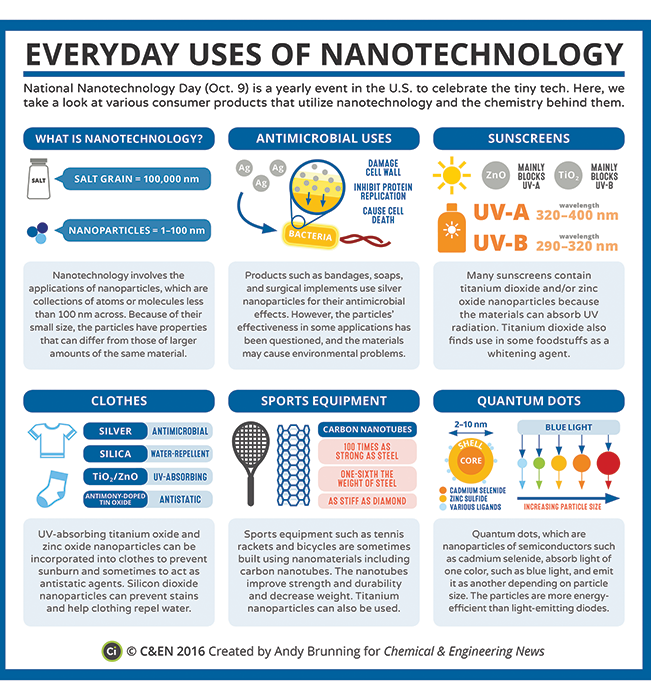

Celebrating All Things Nano

Last updated 9/19/2022

Some of the most marvelous developments of our time come from a single number: 10-9. This number represents all the unique properties, phenomena, and processes scientists have found at sizes between roughly 1–100 nanometers (nm). A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter, roughly the size of 10 atoms. To better understand the scale of a nanometer, consider a single strand of human hair: It’s approximately 80,000–100,000 nm wide. Scientists have been able take advantage of phenomena at the nanoscale to create smaller computers, faster processors, greener catalysts, and new ways to treat deadly diseases. And it’s for this exciting reason that every year on October 9 (10/9), we celebrate National Nanotechnology Day!

Check out these fun ideas to investigate advances in nanotechnology and how they impact our everyday lives.

Nanotech’s creative beginnings

Nanoscale materials have been used for centuries. Although they probably didn’t realize why it worked, 4th century Romans used colloidal gold and silver (metal particles sizes around 10–100 nm) to create glass that changed color depending on the angle light struck the surface. The art evolved into a science in the 19th century when scientists such as Michael Faraday studied how metal colloids produced different colors under certain conditions.

In the 1950s, research into colloids allowed for the development of many materials, including specialized papers, paints, and thin films. A 1959 talk by renowned physicist Richard Feynman planted many of the seeds for nanotechnology; it was essentially a thought experiment about the creation of nanomachines that could directly manipulate atoms. However, because nanoparticles are smaller than the wavelength of visible light (380–750 nm), they cannot be studied with a typical light microscope or other conventional equipment. Therefore, much of the work concerning nanoscale materials remained theoretical until 1981, when the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope enabled researchers to create images of actual nanoparticles.

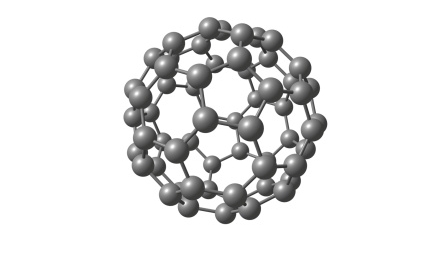

In 1985, Richard Smalley and his colleagues reported the discovery of Buckminster fullerene (C60, aka buckyballs). A brand-new allotrope of elemental carbon, buckyballs exhibited exceptional strength and stability for molecules of their size, as well as unusual electronic properties. Within two years, hundreds of scientists were turning their attention to C60 and exploring other nanoscale materials. The field has been rapidly growing ever since.

According to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), the top five current trends in nanotechnology research are stronger materials and higher strength composites, scalability of production, more commercialization, sustainability, and nanomedicine. For example, the tensile strength of carbon nanotubes and graphene (single atom-thick sheets of carbon) is about 100 times that of steel. Consequently, carbon fibers and nanotubes have found commercial applications in things like helmets, bicycle frames, and car frames (e.g., the Lamborghini Aventador chassis).

Why smaller is better

Nano-sized particles have many different properties from their bulk counterparts, especially metals and inorganic compounds. For one thing, the ratio of atoms on the surface to those inside the nanoparticle is much higher. This means more surface atoms are available for reacting (think more powerful catalysts), and they have fewer interatomic interactions holding them in place (think reduced melting points). Gravity, being mass-dependent, becomes much less important than electromagnetic forces, which support the formation of colloids.

Plus, in metal and semiconductor nanoparticles, properties like color, fluorescence, electrical conductivity, and magnetic permeability become dependent on the precise particle size. In bulk materials (> 100 nm), the highest occupied orbital and the lowest unoccupied orbital of individual atoms overlap and blend together to make energy bands, wherein the gap between the bands—called band gap—governs the material’s optical, electronic, and chemical behavior.

But smaller than 100 nm, the bands are still quantized (unblended), and the size of the band gap increases as the particle size decreases. With such a phenomenon, you can “tune” the properties of the material by creating different particle sizes

Putting nanotech into tech

Nanoscience is ideal for a number of technological applications that improve our daily life. Here are some prime examples:

- To improve energy efficiency, a team of scientists lead by Bingqing Wei at the University of Delaware used carbon nanotubes as electrodes to enhance the storage capability of dielectric capacitors, and researchers at the North Carolina State University have been incorporating silicon-coated carbon nanotubes to increase the capacity of lithium-ion batteries.

- A 2014 review highlighted advances in health, safety, and even smart textiles. Recent developments include flexible materials for wearable electronics and the wearable devices energized by motion.

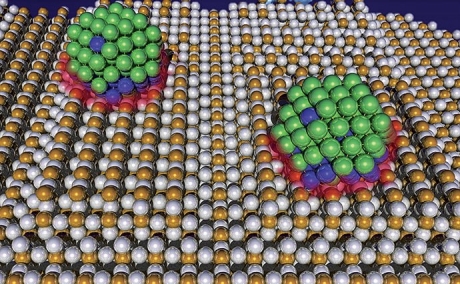

- Opening a completely new field are quantum dots—semiconductor nanoparticles are now being arranged in ordered structures, similar to atoms in a crystal lattice resulting in new applications for LEDs and TV and computer displays. Researchers are also exploring applications for spectroscopy detectors, solar cells, catalysis, and biotechnology. Additionally, quantum dots have electronic properties that parallel those of individual atoms, so ordering these “pseudoatoms” into crystal-like arrays is another area of growing research.

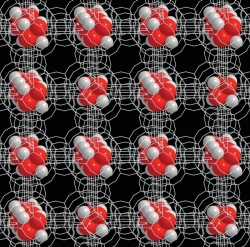

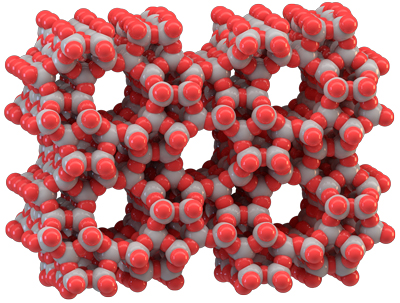

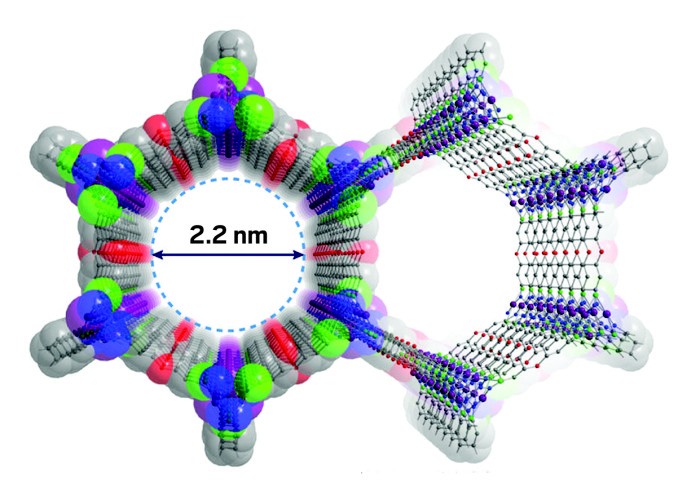

- Nanostructured materials—inorganic or organometallic materials with nano-scaled architecture—have a number of applications. For example, zeolites are crystalline aluminosilicates whose structure includes regular-shaped pores. Because the pores have a specific shape and size, the products of chemical reactions taking place inside them must also have specific shapes and sizes. Many zeolites are already used in industry, and research continues to explore new possibilities, such as new sizes for catalyzing reactions with larger molecules, encapsulating nanoparticles for catalysts and solar cells, and exploring possibilities for non-silicate materials.

Huge medical advances from nanomaterials

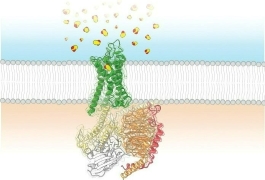

Nanomaterials are the right size for medical applications, since much of biology takes place at a nanoscale. Cell membranes are typically 5–10 nm thick, mitochondria are 1–2 nm long, and water molecules are about 0.2 nm wide.

Here are some amazing ways nanotechnology has improved medical diagnostics, monitoring, and treatments that protect and prolong human life:

- Optical and electronic properties of gold nanoparticles can be tuned by changing the size, shape, surface chemistry, or aggregation state. This has opened doors to for better sensory probes that are used for drug delivery, cancer treatment, and tumor markers. In addition, chirality in nanoparticles is being explored to develop better sensing materials and images to further our understanding of biological processes.

- Carbon nanotubes have been used as sensors for measuring the amount of nitrogen oxide in the blood and artificial muscles. Commercialized applications include nano-sized zirconium dioxide materials used in bone replacements.

- According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), researchers at the Northwestern University Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence (NU CCNE) are using DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles for a variety of high sensitivity biodiagnostic systems for cancer.

Important Risk Considerations

According to the National Institutes of Health, nanomaterials will be have a tremendous impact on society: improving energy usage and transmission, new modes of computing and data storage, new ways to monitor the freshness of food, constructing lightweight, wear-resistant materials for transportation and building, and safer, more effective consumer products. But as with any technology, nanotechnology comes with a price. Working safely with the nanomaterials is a challenge for the exact same reasons as they are exciting—their properties and their size.

Studies show that nanomaterials are easier to inhale and may even stick around in the lungs for a while, raising concerns about the development of airway diseases. And as nanomaterials are used more and more in clothing, beauty products, and electronic devices, unintended release in the environment and bloodstream are concerns that researchers are actively studying to safeguard life and the earth.

For more information about National Nanotechnology Day, visit nano.gov/nationalnanotechnologyday.

Examples of nanomaterials

Nanotechnology encompasses both particles that are less than 100 nm and materials with repeating structures in the 1 – 100 nm range. Here are some examples.