Industrial Hygiene: Making the World Safer One Workplace at a Time

As a chemistry student, you well know that some ways of doing science are safer than others. You know to store the oxidizers separately from the reducers, to wear your goggles in the lab, and to dispose of waste properly. So, when you read about the devastating explosion in Beirut or about deaths at U.S. chemical facilities, you might be asking yourself, “What happened? Don’t they know how to handle these chemicals?”

Sometimes, the answer is “no,” because many industrial employees are not experienced chemists, which is why industrial toxicology and industrial hygiene are vital to workplaces around the world.

Unsafe workplaces and industrial accidents are expensive, bad for business, and most of all, avoidable, with the correct knowledge and preparation. Employers are eager to fill jobs for industrial toxicologists and hygienists, as they are required by federal law. But currently there are not enough people with the proper chemistry backgrounds trained to perform the work.

“All chemicals can be handled safely,” says Harry Elston, founder of the environmental, health, and safety consulting company Midwest Chemical Safety, LLC. “It’s just a matter of how much time, money, effort, and control you want to put into managing your chemicals and reactions.”

Industrial toxicology: Will this kill me?

Although records on work conditions date back to ancient Rome, the modern field of industrial toxicology was established in the early 20th century by Alice Hamilton, a pioneer of industrial medicine. Hamilton, the first woman faculty of any field at Harvard University, was the first to notice that immigrants in Chicago were getting sick from the chemicals they used to glaze ceramics. Hamilton is known for groundbreaking studies into the poisonous effects of several substances, including a landmark study of the use of lead and lead oxide as pigments.

Toxicologists study the safety and biological effects of industrial processes and materials. They examine what happens “from cradle to grave,” examining the impact of how starting reagents are sourced, safety of the reactions, and final disposal of the products and wastes.

About half of toxicologists are true industrial toxicologists, working in industry. The remainder work in government, academia, and consulting firms. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), for example, hires many toxicologists to establish the minimal risk levels for various substances and to coordinate responses to accidental releases of hazardous substances.

Another U.S. government agency is the National Toxicology Program, an interagency partnership of the Food and Drug Administration, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Their scientists conduct research to determine the health ramifications of chemical exposures, and their assessments are often used to help shape public health policies and regulations. Some of the things they are currently investigating as potentially harmful substances include dietary supplements, cell phones, synthetic turf, BPA, and mold.

Industrial hygiene: Are we in compliance?

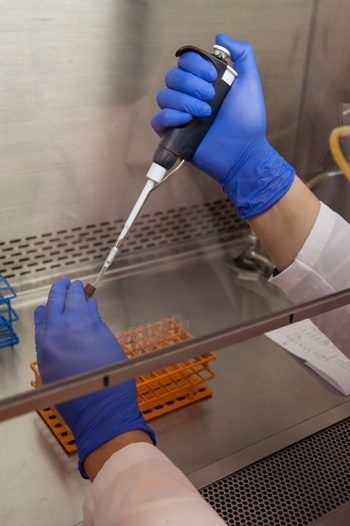

Industrial hygiene is a relatively new field that emphasizes compliance with safety regulations. It relies on toxicology but broadens out to mitigate the harmful exposures that toxicologists identify in different workspaces and situations. Industrial hygienists might take air samples for toxicologists to analyze for harmful substances and then, based on the toxicology report, recommend protective measures such as laboratory ventilation, hoods, and personal protective equipment specifically for a particular lab or plant. Their expertise is invaluable in dealing with the exposures and health risks inherent in natural disasters, terrorist attacks, and the accidental release of dangerous chemical, biological, or radioactive substances. You can learn more about the distinct roles of industrial hygienists versus industrial toxicologists from the Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management site, run by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Suppose an industrial lab is trying to decide between two processes, each with its own safety concerns and costs. Some of the things that might need to be considered include:

- Can the reactants be stored on-site?

- What precautions are needed for safe storage and handling of the reactants and products?

- How can the waste be handled?

- What are the relevant county/state/federal requirements to follow?

- How much will the safety protocols cost?

- What do the workers handling the materials need to know to be safe?

- What happens if the safety protocols fail, and how can failures be prevented?

This is where industrial hygienists come in. “They try to help workers do their jobs safely and right,” says Robert Hill, a former researcher at NIOSH and a past chair of the ACS Committee on Chemical Safety. During his years working at NIOSH, Hill used his chemistry research background to develop analytical methods to measure people’s exposure to toxic chemicals through the air. It was there that he learned how important it is to protect people where they work.

Getting into the safety gig

Many industrial hygiene careers follow nonlinear paths. Hill started out as a researcher for the CDC, where he developed analytical methods to measure exposure to toxic chemicals in blood and urine. This was his initial segue from research chemistry into managing the health and safety of lab workers. He later went on to work for NIOSH and later, he literally wrote the book on laboratory safety, titled Laboratory Safety for Chemistry Students.

Hill did not have formal schooling in industrial hygiene; he gained experience through on-the-job training. “The higher level of management you are,” he says, “the more knowledge you need to have. Industrial hygienists sometimes don’t have enough chemistry to understand what people are doing and help them do things the right way.” He credits his background as a research chemist with giving him credibility when talking to lab researchers about how to minimize their risks.

According to Frankie Wood-Black, founder of Sophic Pursuits Inc., “the same drive and skills that you need for medical school—to help people, to work hard—can put you in this field as well.” And the pay is good. She says that newly minted industrial hygienists can start out earning around $70,000 a year. Add a certificate and that can go up closer to $100,000.

There are a number of schools that offer master’s degree programs in industrial hygiene. Alternatively, the American Board of Industrial Hygiene, the American Industrial Hygiene Association, and the Board of Certified Safety Professionals all offer certifications that bachelor’s level chemists can get while they’re working. ACS offers courses at national meetings as well, although that will probably look a bit different this year.

People skills are a must

You don’t necessarily need an advanced degree to become an industrial hygienist or toxicologist, says Doug Walters, who headed chemical health and safety for the National Toxicology Program. He advises that if you are interested in lab safety, you should contact the chemical safety officer in your chemistry department to learn about their background and what they do. From there you can get directed to the Office of Health and Safety at your university. You can also attend sessions offered by the ACS Committee on Chemical Safety at regional or national meetings.

Elston agrees. He says you need a bachelor’s degree plus experience, or an advanced degree if you have fewer years of experience. “Try to get as much experience as you can in the area you choose,” Elston says. “If you want to do lab safety, you should first work in a lab. If you want to do safety in plants, you should shadow someone working there.”

Researchers and lab managers can fall anywhere on the spectrum from risk-averse to risk-tolerant. This can cause conflict with the industrial hygienist, who must be able to manage all of these personality types when conveying toxicology reports. “You need a passion for people and keeping people safe,” says Elston. “You need to know not only how to control exposures and chemicals but how to get people to do their jobs safely. You don’t want to just be saying ‘no’ all the time.”

Research experience gives you practical insight into how labs work; since academic research is a very different experience from industrial research, time spent in the latter is especially helpful. It also gives you increased credibility with the researchers who must implement your recommendations. Researchers will be more likely to heed your advice if they feel like you know where they’re coming from. “Otherwise,” says Hill, “there can be a communication gap if lab workers think that the safety people don’t understand what they’re doing.”

Walters points out that people skills are also vital because you’ll need to interact with, and learn from, people across many disciplines--such as engineers who design and build lab equipment and lab architects and designers who decide where hoods should be placed.

He speaks from personal experience. When he was in graduate school, he worked with phosphines in an attempt to make a phosphorus analog of EDTA (a feat that has still not been accomplished). Phosphenes are toxic, spontaneously combustible in air, and smell vile, so he was not the most popular guy in the lab.

After a number of fires, a wise professor counseled him to call plant maintenance to get his hood checked. It turned out that a fan blade was corroded by acid from a previous user. Walters thus got first-hand and early knowledge of what he deems the biggest problem in safety: lab ventilation, air flow, and hoods. He went on to design balance exposures so people could precisely weigh toxic chemicals with the protection of the hood but without blowing anything around.

Industrial Safety in a COVID-19 World

The COVID-19 pandemic is “highlighting that people don’t understand risk,” says Wood-Black. Because there is insufficient understanding of the chemistry, there are the downstream effects of people poisoning themselves with cleaning supplies that are being used either improperly or simply in larger quantities and with more frequency than ever anticipated.

Understanding risk and minimizing downstream effects are exactly the skills that industrial hygienists and toxicologists are trained to have. They are currently being asked to evaluate masks and how to clean surfaces, areas that may fall outside of their traditional purview—further highlighting that the expertise required to navigate this crisis is sorely lacking.

Walters hopes that the pandemic will change people’s thinking about contamination –“what gets on their hands, how long it stays there, how they can spread it to other people and other parts of their body.” He also notes that toxicologists’ skills are sorely needed in this moment, when it is vital to know when one should wear masks and gloves, to know what those masks and gloves should be made of (“A surgeon’s gloves are useless in a chemistry lab,” he says.), and to understand ventilation systems. The pandemic, and how it has been handled, underscores the importance of science education and literacy in our country, he notes.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration requires all employers to have a health and safety expert, so industrial toxicologists and hygienists are in high demand. Want to make the workplace safer? This could be the career for you.