Norbert Rillieux and the Multiple Effect Evaporator

Dedicated April 18, 2002 at Dillard University in New Orleans, Louisiana

Norbert Rillieux (1806-1894), widely considered to be one of the earliest chemical engineers, revolutionized sugar processing with the invention of the multiple effect evaporator under vacuum. Rillieux’s great scientific achievement was his recognition that at reduced pressure the repeated use of latent heat would result in the production of better quality sugar at lower cost. One of the great early innovations in chemical engineering, Rillieux’s invention is widely recognized as the best method for lowering the temperature of all industrial evaporation and for saving large quantities of fuel.

Contents

Norbert Rillieux: Chemist and Engineer

The birth record on file in New Orleans City Hall is spare: “Norbert Rillieux, quadroon libre, natural son of Vincent Rillieux and Constance Vivant. Born March 17, 1806. Baptized in St. Louis Cathedral by Pere Antoine.”

Vincent Rillieux was an inventor himself who designed a steam-operated press for baling cotton. He appears to have had a long relationship with Constance Vivant, “a free woman of color,” and one of their sons, Norbert, became what is now called a chemical engineer. The use of the father’s surname and the baptism in New Orleans’ cathedral indicate the paternity was publicly acknowledged.

As a boy the precocious Norbert showed an interest in engineering, and his father sent him to France for his education. By the age of 24, Rillieux was an instructor in applied mechanics at the Ecole Centrale in Paris. Around 1830, Rillieux published a series of papers on steam engines and steam power.

While in France, Rillieux began working on the multiple effect evaporator. As George Meade, a sugar expert, wrote in 1946: “The great scientific contribution which Rillieux made was in his recognition of the steam economies which can be effected by repeated use of the latent heat in the steam and vapors.” What Rillieux did, and what became the basis for all modern industrial evaporation, was to harness the energy of vapors rising from the boiling sugar cane syrup and pass those vapors through several chambers, leaving in the end sugar crystals.

Rillieux’s evaporator was a safer, cheaper, and more efficient way of evaporating sugar cane juice than the method then in use, the Jamaica train. In this system, teams of slaves ladled boiling sugar juice from one open kettle to another. The resulting sugar tended to be of low quality since the heat in the kettles could not be regulated, and much sugar was lost in the process of transferring juice from kettle to kettle.

Some Louisiana sugar planters quickly understood the significance of Rillieux’s invention, and he returned to New Orleans in the early 1830s, years that coincided with a sugar boom. Rillieux tinkered with his invention over the next decade, and in 1843 he was hired to install an evaporator on Judah Benjamin’s Bellechasse Plantation. Benjamin, a Jewish lawyer who later served as secretary of war in the Confederacy, became Rillieux’s staunchest supporter in Louisiana sugar circles. Benjamin wrote in 1846 that sugar produced with the Rillieux apparatus was superb, the equal of “the best double-refined sugar of our northern refineries.”

The success of his evaporator apparently made Rillieux, according to a contemporary, “the most sought after engineer in Louisiana,” and he acquired a large fortune. But while his invention no doubt enriched sugar planters, Rillieux was still, under the law, “a person of color” who might visit sugar plantations to install his evaporator but who could not sleep in the plantation house. (Nor, for that matter, could a man of Rillieux’s accomplishments be expected to stay in slave quarters. Some planters, it appears, provided Rillieux with a special house with slave servants while he visited as “a consultant.”). As the Civil War approached, the status of free blacks deteriorated with the imposition of new restrictions on their ability to move about the streets of New Orleans and other draconian laws.

It was about this time that Rillieux moved back to France. Race relations may have played a part in his decision. At one point, Rillieux became incensed when one of his applications for a patent was denied initially because authorities mistakenly believed he was a slave and thus not a citizen of the United States. The declining profitability of the sugar industry in Louisiana also may have been a factor. In any event, in Paris, Rillieux developed a passion for Egypt. In 1880, a visiting Louisiana sugar planter found Rillieux deciphering hieroglyphics at the Bibliotheque Nationale. Rillieux died in 1894 and was buried in the famed Paris cemetery of Pere Lachaise. His wife, Emily Cuckow, lived comfortably for another eighteen years.

I have always held that Rillieux’s invention is the greatest in the history of American chemical engineering and I know of no other invention that has brought so great a saving to all branches of chemical engineering.”

— Charles A. Browne (1870-1947), Sugar Chemist, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Sugar Production and the Multiple Effect Evaporator

Sugar cane had been planted as early as 1750 near New Orleans, but with only limited success. Throughout most of the eighteenth century indigo, a blue dye, was Louisiana’s cash crop, but the ravages of disease and insects forced planters to look for alternatives. By the 1790s, interest in sugar revived. Production rose steadily thereafter, and by 1830 Louisiana was producing over 33,000 tons of sugar annually.

Sugar cane is normally harvested in the fall. After cutting, the cane is milled to produce sugar cane juice. Originally animal power was used to grind the cane; by the 1830s, steam power began to replace animal power. In either case, the cane juice was boiled in four large open kettles arranged in a kettle train. Each kettle was of different size, and the kettles were arranged from the largest, which held up to five hundred gallons, to the smallest. The first kettle, the largest one, was called the grande, the next the flambeau, then the sirop, and finally, the smallest, the batterie.

In the first kettle, the grande, the juice was brought close to the boiling point, and, as water boiled off, teams of slaves ladled the resulting concentrated sugar syrup to the next kettle. The process was repeated from the flambeau to the sirop kettles. When the syrup thickened and reached the proper quality and density, it was transferred to the batterie. Additional manpower was needed at each step in the process, which was repeated over and over. As soon as one kettle was emptied, its contents were replenished with juice from the kettle that preceded it in the train.

The sugar maker oversaw the syrup boiling in the batterie. When it reached the proper temperature and the right consistency, he would make a “strike.” At that moment, when the boiling mass began to produce sugar crystals, the sugar maker ladled the syrup into vats to cool. If the strike occurred at the right time, the syrup would crystallize; if not at the right time, the syrup would cool into a mass of worthless molasses.

This process, the Jamaica train, was primitive because it required the constant attention of teams of slaves performing tedious, backbreaking, and dangerous manual labor; wasteful because much sugar was lost in the process; and inefficient because each kettle required its own source of heat, usually wood, and because the heat could not be regulated. Various attempts, with only partial success, had been made to harness the energy of the steam rising from the boiling juice to heat the liquid in the next step in the refining process.

Norbert Rillieux’s great innovation was his understanding of how latent heat could be used repeatedly in processing sugar. The result was his Multiple Effect Evaporator under Vacuum, which one expert, John Heitman in The Modernization of the Louisiana Sugar Industry, 1830-1910, called “the premier engineering achievement in nineteenth-century sugar technology.” Others have described Rillieux’s design as revolutionizing the sugar industry much as Eli Whitney’s gin revolutionized the processing of cotton.

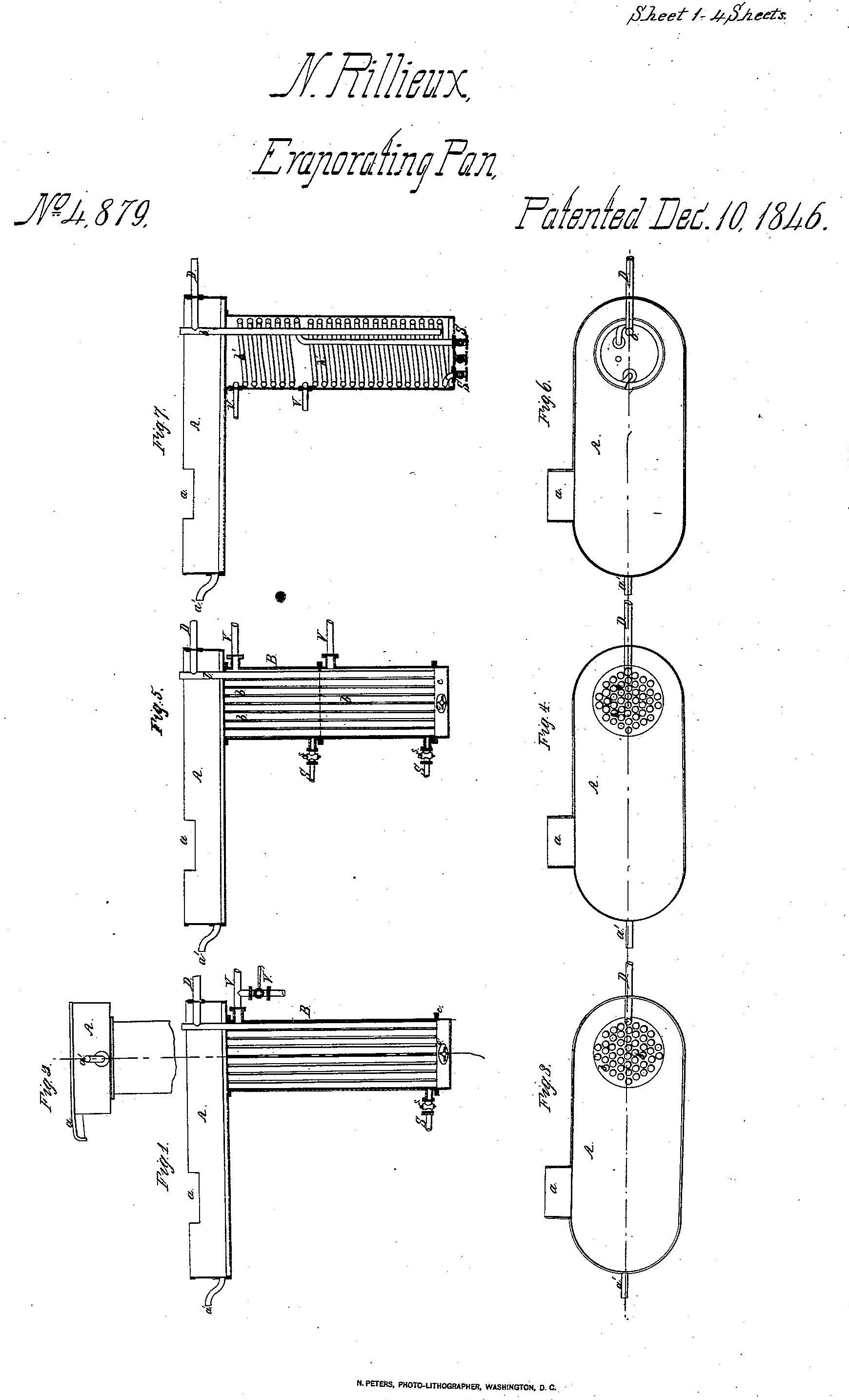

Rillieux utilized the latent heat produced from evaporating sugar cane juice by employing a series of three or four closed evaporating pans in which vapor was piped out of each pan to heat the juice in the next, with the vapors in the end going to a condenser. At the same time, pressure in the system was reduced by pumps, which created partial vacuums and lowered the boiling point of the liquid. A description of the invention’s design is given in Rillieux’s 1846 patent:

“A series of vacuum pans, or partial vacuum pans, have been so combined together as to make use of the vapor of the evaporation of the juice in the first, to heat the juice in the second and the vapor from this to heat the juice in the third, which latter is in connection with a condenser, the degree of pressure in each successive one being less… The number of sirup-pans may be increased or decreased at pleasure so long as the last of the series is in conjunction with the condenser.”

Rillieux’s invention allowed for the production of better quality sugar with less manpower and at reduced cost. One of the major economies was the conservation of fuel, because wood was needed to heat only the first chamber. Each successive chamber used the latent heat released by steam from the preceding chamber. But even though the Rillieux evaporator marked a significant advance in sugar technology, some antebellum Louisiana planters were reluctant to install the devices.

The reasons had to do with the inherent contradictions in slavery. Many planters thought slaves incapable of operating sophisticated equipment. Other planters believed that teaching slaves new skills might lead to their questioning authority, which in turn could lead to rebellion. One slaveholder, Andrew Durnford, himself a free black, refused to install a Rillieux evaporator because he did not want to “give up control of his people.”

In the end, however, sugar manufacturers around the world in Cuba, Mexico, France, and Egypt, as well as the United States, adopted Rillieux’s evaporator. Moreover, the device was not limited to sugar production but came to be recognized as the best method for lowering the temperature of all industrial evaporation and for saving large quantities of fuel. Multiple effect evaporation under vacuum is still used in sugar production as well as in the manufacture of condensed milk, soap, glue, and many other products.

The Rillieux evaporator was one of the earliest innovations in chemical engineering and remains the basis of all modern forms of industrial evaporation. It is perhaps most extraordinary that Rillieux invented his device before the Civil War, at a time when the vast majority of African Americans were enslaved. He was successful because he understood the principles of thermodynamics and latent heat and applied that knowledge to the technical needs of the sugar industry.

Norbert Rillieux and the New Orleans "gens de couleur libre"

Americans pouring into the newly purchased Louisiana Territory encountered a social caste virtually unknown in the Eastern seaboard States: gens de couleur libre, free people of color. In the early years of the nineteenth century, free blacks comprised 25 percent of the population of New Orleans, far higher than in most other areas of the American South, where nearly all blacks were slaves.

The number of free blacks in New Orleans was due in part to the French and Spanish heritage of Louisiana. Both France and Spain had lenient manumission policies and both encouraged slaves to purchase their freedom. But the majority of free blacks resulted from sexual relations between white men and black women. One Spanish bishop lamented, “a good many inhabitants live almost publicly with colored concubines” and they consider the issue of such liaisons “as their natural children.” Finally, the ranks of the gens de couleur libre swelled in the early years of American control of New Orleans with the influx of thousands of light-skinned freemen fleeing the internecine warfare in the new black Republic of Haiti.

In the eighteenth century, Louisiana free blacks enjoyed a higher social status and had more rights than the small free black population of the English colonies. Their condition would deteriorate under American control, but it remained true that free blacks maintained a privileged status in the antebellum years. As late as 1856, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that under Louisiana law there is “all the difference between a free man of color and a slave, that there is between a white man and a slave.” Indeed, a few free blacks even belonged to the planter class, owning slaves themselves.

In nineteenth century New Orleans, as in the years of French and Spanish rule, relationships between white men and black women were common. Harriet Martineau, the noted English novelist, social critic, and traveler, expressed shock at New Orleans social mores: “The quadroon girls of New Orleans are brought up by their mothers to be what they have been, the mistresses of white gentlemen.” Martineau noted that many of the sons were sent to France, as was Norbert Rillieux.

In many cases, white men and “free women of color” formed strong attachments and, as Frederick Law Olmsted, the famous landscape architect who visited New Orleans in the 1850s, noted: “The arrangement is never discontinued, but becomes, indeed, that of marriage, except that it is not legalized nor solemnized.” Such appears to have been the case with Victor Rillieux, who never married, and Constance Vivant. But Olmsted also wrote of the alienation of “the class composed of the illegitimate offspring of white men and colored women (mulattoes or quadroons), who, from habits of early life, the advantages of education, and the use of wealth, are too much superior to the negroes, in general, to associate with them, and are not allowed by law, or the popular prejudice to marry white people.”

This was the world of Norbert Rillieux, a world in which the large caste of “free people of color” had rights intermediate between slaves and whites. They were, in other words, neither slave nor free.

Norbert Rillieux and Edgar Degas

The great French impressionist painter, Edgar Degas, visited New Orleans in 1872, a time when the city, still recovering from the ravages of the Civil War, was in the throes of Reconstruction and under Federal control. Degas’ productivity as a painter had stalled, but something about the war-torn and divided city gave him new inspiration and elicited some of his finest paintings.

The primary reason for Degas’ trip was to spend a few months with the American branch of his family. The painter’s great grandfather, Vincent Rillieux, had built a large house on Royal Street. His daughter Maria was Degas’ maternal grandmother.

A well-kept secret of the Rillieux clan was the liaison of one of Vincent’s sons, also named Vincent, with Constance Vivant. Two of their sons — first cousins of Degas’ mother - were Edmond, who became superintendent of the New Orleans water works, and Norbert, the chemist and engineer.

Research Notes and Further Reading

Research Notes

Benfey, Christopher, Degas in New Orleans: Encounters in the Creole World of Kate Chopin and George Washington Cable, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997.

Benfey, Christopher, “Norbert Rillieux: Chemical Engineer and Free Black Cousin of Edgar Degas,” Chemical Heritage: Newsmagazine of the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Summer 1998, Vol. 16, No. 1, 10-11, 38-40.

Berlin, Ira, Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South, New York: Pantheon Books, 1974.

Conrad, Glenn R. and Ray F. Lucas, White Gold: A Brief History of the Louisiana Sugar Industry, 1795-1995, Lafayette, LA: University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1995.

Deerr, Noel, The History of Sugar, 2 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1949.

Elder, Eleanor, “The Rillieux Plaque in the Cabildo,” Chemical Heritage: Newsmagazine of the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Summer 1998, Vol. 16, No. 1, 41.

Heitman, John Alfred, The Modernization of the Louisiana Sugar Industry, 1830-1910, Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1987.

Meade, George P., “A Negro Scientist of Slavery Days,” Scientific Monthly, 1946, Vol. LXII, 317-326. Reprinted in Negro History Bulletin, April 1957, Vol. XX, 159-163.

Olmsted, Frederick Law, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States, New York: Dix and Edwards, 1856.

Further Reading

Landmark Designation and Acknowledgments

Landmark Designation

The American Chemical Society designated the invention of the multiple effect evaporator under vacuum by Norbert Rillieux as a National Historic Chemical Landmark in a ceremony at Dillard University in New Orleans, Louisiana, on April 18, 2002. The plaque commemorating the designation reads:

Norbert Rillieux (1806-1894) revolutionized sugar processing with the invention of the Multiple Effect Evaporator under Vacuum. Rillieux’s great scientific achievement was his recognition that at reduced pressure the repeated use of latent heat would result in the production of better quality sugar at lower cost. One of the great early innovations in chemical engineering, Rillieux’s invention is widely recognized as the best method for lowering the temperature of all industrial evaporation and for saving large quantities of fuel.

Acknowledgments

Adapted for the internet from “Norbert Rillieux and a Revolution in Sugar Processing,” produced by the National Historic Chemical Landmarks program of the American Chemical Society in 2002.

Back to National Historic Chemical Landmarks Main Page.

Learn more: About the Landmarks Program.

Take action: Nominate a Landmark and Contact the NHCL Coordinator.