What's Artificial Snow and How Is It Made?

Winter snowfalls herald all manner of fun and games: snowball fights, skiing, tobogganing, snowboarding, and, every four years, couch potato-ing as people all over the world watch the Winter Olympics. But what’s a winter sports enthusiast to do if the coveted precipitation doesn’t make an appearance?

That’s where artificial snow comes in.

Using machines to make snow is commonplace for outdoor winter sports, including downhill skiing and snowboarding. Ski resorts, hoping to extend the season or simply enhance existing natural snow, pump water and pressurized air uphill to “snow guns” stationed along the slopes. The snow guns atomize the water and spray out a long plume of fine droplets, which, hopefully, freeze before hitting the ground.

In 1980, the Olympics held in Lake Placid, N.Y., became the first Winter Games to use machine-made snow, but they were not the last. Artificial snow also made an appearance at the two most recent Winter Olympics, in Sochi, Russia (2014), and Vancouver, British Columbia (2010).

With the approach of the 2018 Olympics in South Korea, snow guns are standing by at Jeongseon Alpine Centre, the site of the games’ alpine speed events, according to the website of manufacturer SMI. And the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing will have to rely almost entirely on snowmaking to offset the region’s minimal precipitation.

As long as the temperature remains below about –8 °C, snow guns can readily produce as much snow as needed. When the thermometer reads higher, the water needs a little help to freeze.

Natural snow forms in clouds when water molecules organize around a nucleator, a particle that acts as a scaffolding to “kick-start” ice crystal formation, says Daniel Cziczo, an atmospheric chemist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. These nucleators often have a hexagonal binding structure that mimics that of water, although the hexagonal structure may not be required. Once the binding gets started, the rest of the water molecules begin to knit together as ice, Cziczo says. Mineral dust, clay particles, and even bacteria can all serve as nucleation sites.

Earthbound snow guns, however, don’t always have the benefit of the atmosphere’s cold temperatures. Thus, makers of artificial snow have borrowed some nucleation ideas from on high to help water freeze more rapidly at higher temperatures.

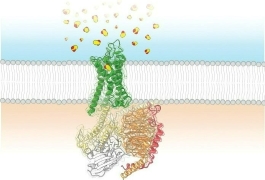

One such product is Snomax, a freeze-dried protein powder sold by Snomax International of Englewood, CO, is mixed into the water pumped uphill to snow guns. Snomax derives its nucleating ability from Pseudomonas syringae, a bacterium commonly found on agricultural crops and other plants as well as in the atmosphere. P. syringae has a powerful nucleating protein on its cell surface, with which it creates an icy spear to pierce plant cells and then feast upon their contents.

Drift, a snowmaking additive launched in 2001 by Aquatrols of Paulsboro, N.J., is a liquid polyether-substituted trisiloxane that acts as a surfactant. By reducing the surface tension of the water sprayed out of snow guns, this surfactant helps the droplets freeze more rapidly rather than clump together, says Andy Moore, the sales director for Drift. This ability helps increase the high-temperature window for snowmaking by about 1 °C and can improve snow quality at lower temperatures, he says.

“What we do is real snow,” Moore points out. “We’re just helping to make it.”

Adapted from “What’s artificial snow, and how is it made?”, originally published in Chemical & Engineering News. Hiolski, E. C&EN 2018, 96 (6), 20-21.