Psychedelic Drugs Offer Hope for Addiction, Post-Traumatic Stress

Psychedelic drugs were studied for medical uses in the 1950s and 1960s before being banned in the 1970s. Now researchers are looking again to the compounds as possible treatments for patients that do not respond to conventional therapies for mental health conditions. Read on for some of the research underway with five common psychedelics.

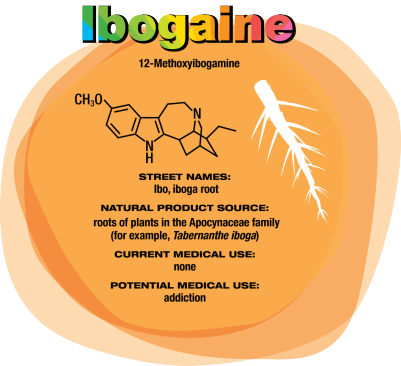

Ibogaine Could Treat Drug Addiction

In the early 1990s, University of Miami neurology professor Deborah C. Mash traveled to Amsterdam to see ibogaine treatments firsthand. “A single dose of ibogaine could completely block the signs and symptoms of opiate withdrawal,” says Mash, who has spent her career studying the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. She and others are now studying ibogaine as a treatment for opiate, cocaine, alcohol, and nicotine addiction.

Ibogaine was first isolated in 1901. It interacts with glutamate receptors in the brain that are involved in learning, memory, and creation of new neural pathways. The receptor interactions are likely the source of ibogaine’s consciousness-altering effects.

But ibogaine is metabolized within 24 hours: A hydroxyl replaces ibogaine’s methoxy group, producing noribogaine. Noribogaine binds to serotonin transporter, opioid, and nicotinic receptors and is cleared from the body slowly. Consequently, noribogaine is likely the compound that’s responsible for reducing patients’ withdrawal symptoms and cravings over the long term, as well as the accompanying anxiety and depression (Neuropharmacology 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j. neuropharm.2015.08.032).

Mash has patented noribogaine and related compounds, as well as their formulations. She founded a company, DemeRx, to bring them into clinical treatment. DemeRx is currently running a Phase II clinical trial to evaluate noribogaine’s use as an alternative to methadone or Suboxone to help opioid addicts transition to sobriety in combination with support for behavioral changes.

Marijuana

“There is a very, very broad range of medical conditions for which cannabis or its constituent chemicals could find applications,” says Daniele Piomelli, a professor of neuroscience and pharmacology at the University of California, Irvine. However, few good clinical studies have been completed. Mammals naturally make some cannabinoids, including anandamide, which likely plays a role in stress response and social behavior, and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, which is involved in modulating activity at the brain’s nerve cell junctions.

Other cannabinoids, such as those produced in marijuana, can target the same neurological receptors as endogenous cannabinoids. Tetrahydrocannabinol is the one that generates a psychoactive response. It is already approved as dronabinol to treat nausea in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy and appetite loss in people with AIDS. However, Piomelli notes it has poor bioavailability and has a complex metabolism.

Researchers are studying another cannabis compound, cannabidiol, to treat seizure disorders, schizophrenia, and other conditions. Cannabidiol is not psychoactive, but unraveling its pharmacology is difficult because it interacts with a variety of receptors beyond the endocannabinoid system.

California’s Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research has studied smoked or vaporized cannabis to treat neuropathic pain, which originates in damaged nerve fibers (J. Pain 2015, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.008). Short-term pain studies indicate that cannabis relieves the pain, "but what we haven’t answered is whether it works forever," says Igor Grant, director of the center and a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. “Does the efficacy remain, or do people get used to it and it no longer works as well? Is it possible that after a year you see side effects that you don’t see after a few weeks?”

With broadening legalization of medical and recreational marijuana in the U.S., Piomelli says, "We typically hear about positive favorable effects because those tend to surface, but we don’t have studies that are done appropriately for all these different uses."

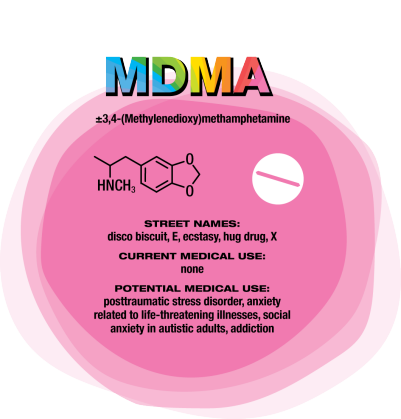

MDMA

“After 100 years of modern psychiatry, our current best treatment for trauma-related disorders is only effective for 50% of people,” says U.K. psychiatrist Ben Sessa. The cure for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is psychotherapy — talking through and processing the trauma with a mental health specialist. “About half of people will talk and, over weeks or months, will overcome their high level of distress and get better,” Sessa says. For others, talking about their experience is overwhelming. “They drop out of treatment and use dangerous drugs such as alcohol to mask their symptoms. They have high levels of self-harm and high levels of completed suicide,” Sessa says.

MDMA interacts with a transporter in the brain that causes the release of serotonin, which in turn causes the release of other neurotransmitters and hormones. For people who might otherwise flee psychotherapy, MDMA reduces fear and increases trust and empathy. MDMA is also mildly stimulating rather than sedating. The overall effect is to calm patients and help them engage with a therapist about difficult experiences. Sessa likens MDMA to a life jacket.

U.S. psychiatrist Michael Mithoefer leads clinical trials studying MDMA for PTSD. In an initial trial, Mithoefer and colleagues worked with patients who had PTSD for an average of 20 years, mostly from sexual trauma. The patients had undergone previous psychotherapy for an average of almost five years and were not helped by conventional antidepressants. They received MDMA or a placebo two to three times, with doses one month apart, as part of eight-hour sessions with two therapists followed by an overnight stay at the clinic for continued monitoring (J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, DOI: 10.1177/0269881110378371)

Going through the psychedelic experience, patients could focus inward and stay quiet as they wished or talk with the therapists. They also had extensive preparatory and follow-up psychotherapy sessions. Of 12 patients who received MDMA, 10 of them (83%) showed significant relief of their PTSD symptoms. In the placebo group, only two out of eight patients (25%) showed improvement with the same psychotherapy support.

Other studies show similar positive results, although “it is hard to have an effective ‘blind’ with this type of substance,” Mithoefer concedes, because patients can usually tell whether they’ve been given a placebo or the real thing.

Nevertheless, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies aims to start Phase III trials for PTSD next year, with MDMA synthesized by an unnamed U.K. contract manufacturing company following current Good Manufacturing Practices.

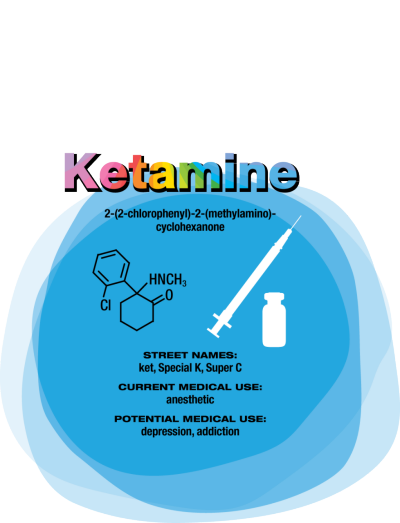

Ketamine

Compared with conventional antidepressants, ketamine is “remarkable,” says David Feifel, a professor of psychiatry and director of a center specializing in advanced treatments for depression at the University of California, San Diego.

Starting in 2004, Carlos A. Zarate Jr., chief of the Experimental Therapeutics & Pathophysiology Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health, led a study in which his team used ketamine to treat 17 patients who had already been through an average of six antidepressants. They observed 12 patients (71%) improve within 24 hours.

That speedy response time contrasts with conventional antidepressants such as sertraline and fluoxetine, which target serotonin pathways in the brain and typically take weeks to work. Ketamine binds to the same glutamate receptors as ibogaine. Its half-life in the body is two to three hours. But ketamine’s relief of depression lasts an average of around seven to 18 days, with some patients improving for as long as five months, Feifel says. Zarate is conducting a range of studies — including neurological imaging, proteomics, and metabolomics — to unravel ketamine’s effects in the brain. He points to dehydronorketamine as a particularly interesting metabolite. Zarate and colleagues have found that it may play a role in alleviating depression by interacting with a nicotinic receptor involved in long-term memory (Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.023).

A racemic mixture of ketamine enantiomers is currently approved and manufactured for use as an anesthetic. Doctors administer it for depression off-label as an injection or intravenous infusion, at a dose low enough to avoid unconsciousness. Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen R&D unit has an intranasal formulation of the S-(+)-ketamine enantiomer, known as esketamine, in clinical trials. In both cases, patients are dosed in clinics and monitored until the altered consciousness effects dissipate. Allergan is developing a related compound, rapastinel, that targets the same glutamate receptors but does not induce altered consciousness.

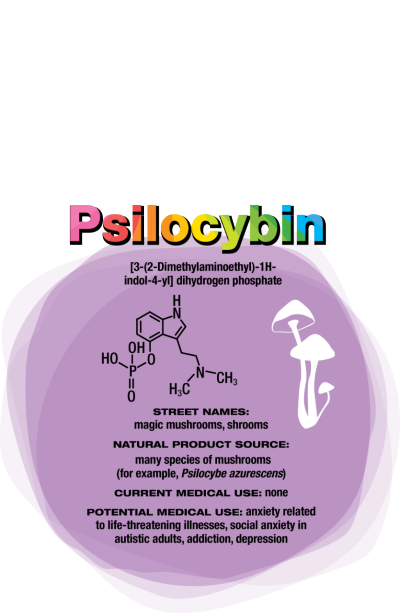

None of the compounds provides a single-dose cure for depression—they all require continuing treatment. Nevertheless, they could be a much-needed help when other treatments do not work. “It was unlike anything I’ve seen in psychopharmacology before,” says Roland R. Griffiths, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, of his first trial examining the safety of psilocybin in healthy volunteers.

Those volunteers had positive effects that could last for years. “People had increased satisfaction and quality of life,” Griffiths says. “They felt more generous, centered, optimistic, and caring toward other people in their lives.” Patients’ friends, family members, and work colleagues confirmed the differences. Griffiths has since conducted trials of psilocybin for tobacco addiction, anxiety, and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer.

Psilocybin

Like MDMA, psilocybin targets serotonin receptors. Also like MDMA, the effects of psilocybin seem to stem from patients’ experiences when their consciousness is altered. But instead of undergoing psychotherapy during the acute psilocybin experience, researchers encourage patients receiving psilocybin to focus inwardly and process their experience with a therapist afterward.

“The best treatment outcomes are with those subjects who, during the course of the psilocybin session, had what they described as a profound psychospiritual epiphany,” says Charles Grob, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the

University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine and chief of child and adolescent psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011, DOI: 10.1001/ archgenpsychiatry.2010.116).

Cigarette smokers given psilocybin report that the drug helps them understand their nicotine craving. That makes them able to quit more successfully when they’re also undergoing a cognitive behavioral therapy program for tobacco addiction, Griffiths says (J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, DOI: 10.1177/0269881114548296).

For people diagnosed with cancer and struggling with the existential fears associated with dying, “it’s harder to say what the nature of the attitude shifts are,” Griffiths says. “But it seems to be an increased sense of wonder and openness to the mystery of life and death. In spite of the tragedy that they’re dying, they might see that there’s something beautiful and organic about the process.”

This article was adapted from "Psychedelic compounds like ecstasy may good for more than just a high," Chemical & Engineering News. 94 (13) March 28, 2016, pp. 28-32.