Distilling Lessons from a Whiskey Research Program

"It always seems impossible until it's done." So said Nelson Mandela, the South African anti-apartheid revolutionary who served as president from 1994–1999. But some things truly are impossible, right? Well, not at Lorain County Community College (LCCC) in Elyria, OH. We’ve been able to launch a graduate-level research program at a two-year college.

It’s challenging enough for four-year colleges to offer substantial research experiences to students with 3–4 years of experience under their belt, but at Lorain, students are using gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) to characterize flavor compounds in unprecedented flavors of bourbon whiskey.

So, how did we pull off modeling graduate research for our students? It was all a matter of being open to the opportunities around us. What follows is our story, and some lessons about spotting opportunities that could help you achieve what seems impossible.

Why being early is better than being on time

It all started very innocently. A former student told me at a campus picnic that he had just completed an inspiring internship at the nearby Cleveland Whiskey distillery. Of course, a whiskey company would need chemical engineers, I thought. So I followed my instincts, and during a brainstorming session for the local Cleveland Section of the Society for Applied Spectroscopy (SAS), I chimed in the idea to visit a whiskey maker for a future group activity. Had I not stayed active with SAS (and, as you will learn later, my other professional society, the ACS), I would’ve missed an opportunity to build on my hopes.

On the heels of my suggestion, we organized a tour of Cleveland Whiskey. I arrived early that evening since I had arranged the tour, and I was pleased to be greeted at the door by the founder and CEO of the company, Tom Lix. Tom would be our tour guide. By arriving early, I had time for a pleasant chat that became a major game changer for our chemistry program.

Say yes to good opportunities – even if you don’t have all the pieces

I introduced myself, and when I told him that I was a chemistry professor at LCCC, Tom immediately suggested that we collaborate on a joint research project using GC-MS to study some new whiskey flavors he was experimenting with. How did he know about GC-MS? I wondered. He’s not an analytical chemist. It was apparent that Tom took time to self-educate in order to strengthen his business and support the work of his employees.

I quickly replied, “Yes, let’s establish a joint research project,” although I honestly didn’t know what we would do or how we would do it. All I knew was that we had to do it.

Every little bit counts

Working with Cleveland Whiskey would give students practical experience, relevant to local industry. It would also be easy for students to understand the applications of the research. But first we needed the equipment, space, and other operational plans for doing the work on our campus.

We would also need funding. So, we started applying for grants. (Note: Grant writing is a major component of graduate research, too.) Our first grant proposal was to the ACS Collaborative Opportunities Grants program. Winning this funding award gave us reassurance that we were doing something worthwhile, and it inspired us to forge ahead.

We proceeded by submitting two more grant proposals — one to the ACS Two-Year College Faculty/Student Travel Grants program, and another to the Center for Teaching Excellence at LCCC. We ended up winning those, too! Despite the fact that all of these grant awards were modest, collectively we were beginning to put together something substantial.

Invest in the people you work with

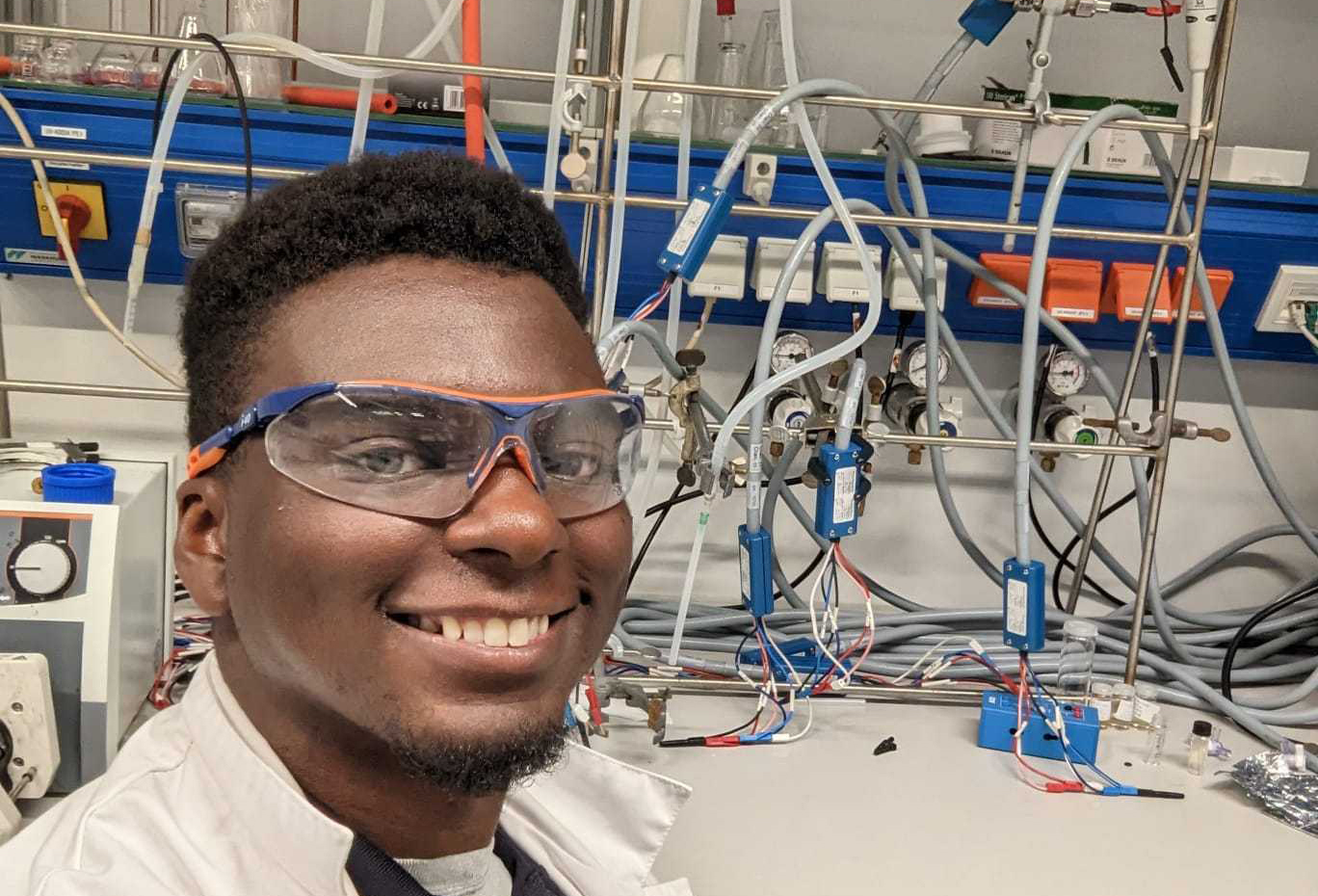

At a community college with 15,000 students and virtually no chemistry majors, how would I recruit students to participate in a chemistry research project and motivate them to produce results? Money! Money is a great incentive, especially for students on shoestring budgets.

Another grant opportunity met this need. This semester, every student in my group is working under a full scholarship, thanks to the NASA Community College STARS Program. Needless to say, each of the students is thrilled to work on the project.

Your current friends are your future collaborators

As a teacher, I knew my responsibility in this research effort was to teach my students how to analyze bourbon whiskey for flavor compounds. The problem was, I didn’t know how to do it myself. How would I know? I’d never done it before.

I turned to Coleen McFarland, a friend from college and a senior analytical chemist at Envantage, Inc., a premier analytical testing lab. Not only did Coleen’s company have substantial expertise in the area, it was also a true pleasure to work with a trusted friend. It was a most valuable validation for why it’s important to stay close with your friends from college. They are your future collaborators, job references, sources for insider tips and opportunities, and so much more.

Build on prior knowledge to get new results

At LCCC, we now get to do research using samples of experimental whiskey flavors that are not yet commercially available. Using GC-MS, we profile the distinct flavor compounds that are leached from the various woods in these uniquely flavored bourbon whiskies. Thus, we have been able to identify and quantify the flavor compounds for each of these unprecedented bourbons. Because of the applied nature of our research, new students readily understand the work and begin to contribute quickly, generating practical and relevant information for our industry partner, Cleveland Whiskey.

The bottom line: You never know what you can do until you try. Be open to new ideas, use the resources around you, and soon you could also accomplish something that seems impossible.

Cleveland Whiskey: Pioneering Spirits

Traditionally, whiskey is produced by aging a clear, distilled spirit in a charred oak barrel for up to 10 years or more. During this time, the spirit becomes flavored with compounds that leach into it from the charred oak.

At Cleveland Whiskey, CEO Tom Lix has developed an innovative technology that accelerates the aging process of whiskey from a matter of years to just days. Essentially, the process involves placing the new spirit in a stainless steel vessel with pieces of charred wood of a controlled surface area, sealing the vessel, and subjecting the headspace above the liquid to a precisely defined cycling of pressure. This forces the alcohol into the wood, extracting compounds from the wood that naturally flavor the whiskey. The company has also begun using the technology to experiment with other new flavors, including bourbon aged naturally with cherry, apple, hickory, maple, and honey locust woods.