Career Ladder: Amber Wise

by Britt E. Erickson, for C&EN

1990s

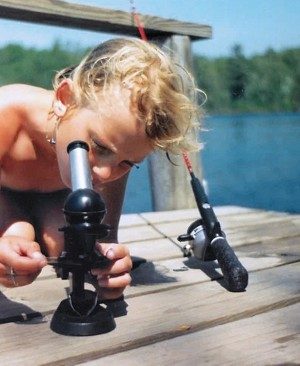

An early love for the lab

Growing up in rural Wisconsin, Amber Wise knew she wanted to be a scientist. Instead of playing house, “my sister and I would play laboratory in our yard,” she says. When she started college at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point in 1997, she studied limnology to learn about freshwater lakes and rivers. But it wasn’t long before her general chemistry professor, C. Marvin Lang, convinced her to switch to chemistry because it offered more job opportunities. “He was totally right,” she says. “That changed my whole career path.”

2003

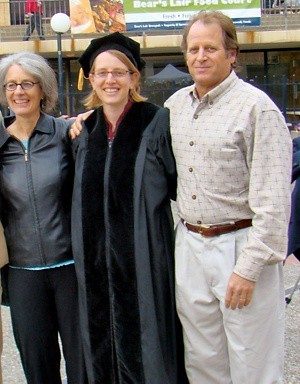

A traditional path to professorship

After earning a BS in chemistry, Wise spent a year as a lab technician, working with graduate students and postdocs. “It made me realize I wanted to do more,” she says. “I wanted to be a professor.” In 2003, she began her chemistry PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, where she studied lipid bilayer interactions on cell surfaces. After completing her PhD in 2008, she worked for a few months on scientific integrity issues at the Union of Concerned Scientists, an advocacy organization, in Washington, DC. Wise then spent more than a year as a postdoc at the University of California, San Francisco. She worked on various projects, such as investigating the reproductive health effects of everyday chemical exposures, which made her consider a career in policy. But after each project, “I felt like nothing is going to change” the government, she says.

2010

Teaching women in Bangladesh

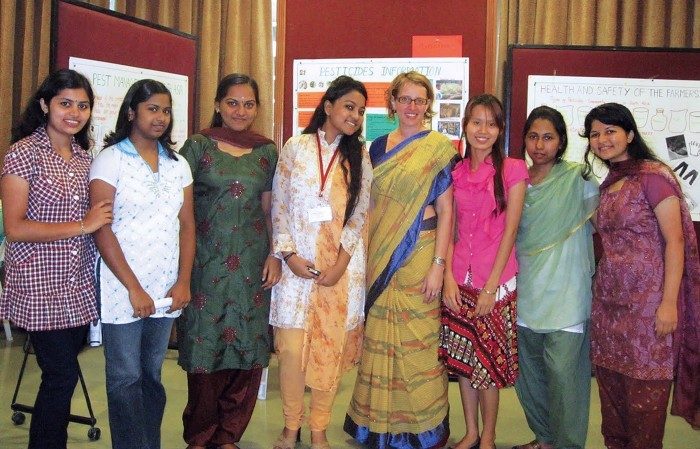

Wise with a group of Asian University for Women students who conducted summer research projects on the use of pesticides in rural regions during the summer of 2011 in Bangladesh, India, and Cambodia.

Instead of a career in policy, she decided to pursue a professorship. In 2010, she accepted a position at the Asian University for Women in Chittagong, Bangladesh. The university was in its second year, and Wise and one other professor were the first to teach chemistry there. “I ordered all the glassware and supplies and designed the curriculum from scratch,” she says. “To some degree, the labs you teach are dependent upon the supplies you are able to get.” After three semesters, Wise returned to the US, where she eventually landed a tenure-track position at Chicago State University, a mostly African American, minority-serving institution. In 2016, the university declared a financial emergency, and “everyone was laid off,” she says.

2016

Taking a chance with cannabis

Wise’s husband got a job in Seattle, so she started looking for a job there. At an American Chemical Society meeting in 2016, she heard presentations about cannabis and realized that the industry desperately needed scientists. Wise found a job as a science director for cannabis producer and processor Avitas, where she specialized in extraction technology and quality assurance. Today, she is the scientific director at Medicine Creek Analytics, a cannabis testing lab. She also advises Washington State on changes in the cannabis industry so that regulations are more science based. “It is a super fascinating industry that is growing fast, too fast,” she says. “The rules change a lot, and there needs to be more harmonization across states.”