Finding Your Path as a Chemical Technical Professional

About halfway through college, Jennifer McCulley discovered a new passion: instrumentation. She analyzed metals for a research project using a flame atomic absorption spectrometer, a high-performance liquid chromatograph, and other specialized tools. “I can’t really explain it, but I fell in love with doing that,” she says. She knew that she wanted to use these instruments in industry. And she didn’t want to wait.

After graduating, McCulley went directly into the workforce as a chemical technical professional. She is now a program manager in the Wilmington, DE, office of Agilent Technologies, a company that produces the analytical chemistry instruments that drew her to this work.

The role of a chemical technical professional is both hands-on and essential, says McCulley. “They are the ones actually prepping samples, doing the instrumentation work.” In some cases, she adds, they’re also analyzing data. You’ll find chemical technical professionals in a wide range of fields, including the food, chemical, petroleum, pharmaceutical, and consumer products industries.

If being the go-to person for handling chemicals, conducting experiments, and running analyses appeals to you, it’s time to learn more about how chemical technical professionals keep their labs—and careers—running.

What does a chemical technical professional do?

When McCulley graduated, chemical technology positions were often advertised as “chemical technician” or “technologist” roles. Although these titles are still used, McCulley, the current chair of the ACS Committee on Technician Affairs (CTA), says that the CTA now prefers the term “chemical technical professional.”

This emphasis on “professional” is long overdue, says ACS Career Consultant Joe Martino, an adjunct professor of chemistry at Immaculata University in Pennsylvania, and a past chair of the ACS Philadelphia Local Section. “[Chemical technical professionals] hold important, professional roles in the mission of a company, and emphasizing this point is important.”

Companies today may also use more specialized titles that reflect specific job duties like forensic chemistry lab technician or engineering technician.

Chemical technical professionals typically enter the workforce with an associate's or bachelor’s degree. In some cases, they may have a master’s, says McCulley. “The criteria are [based upon] what you are doing in the day-to-day.”

This day-to-day routine involves logging a lot of lab time. Chemical technical professionals do the bulk of the benchwork for chemistry labs in industry, government, and in some cases even academia. Many chemical technical professionals work in analytical chemistry, running instrumentation extraordinarily well, says Martino. “Their tasks would be to run analyses on different compounds or whatever the company is trying to analyze.”

One of McCulley’s first jobs was at Campbell Soup Company in Camden, NJ. She analyzed the company’s products to determine the correct nutritional information to put on labels using techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy. Today at Agilent Technologies, she talks with customers in a wide range of industries to figure out their analytical needs and then works with R&D teams to tailor products to meet those needs. “I get to see the different instruments that we have and talk to so many customers around the world,” she says.

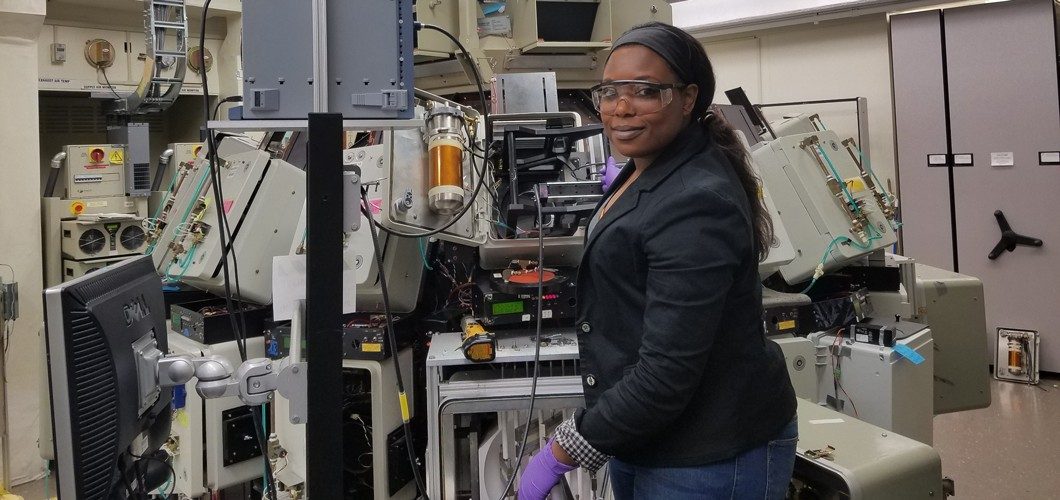

LaKesha Perry began her role as a chemical technical professional analyzing concrete, asphalt binders, and mixers for the Federal Highway Administration (FHA) in McLean, VA. Today, as an engineering technician at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersburg, MD, Perry continues to work with concrete. She runs tests, for example, to understand the hydration reaction chemistry of minerals within concrete mixes. And she studies the viscosity of different mixes of concrete to understand which might work best for 3-D printing. Perry also works with polymers, exposing them to a tool that simulates the sun and then running structural, mechanical, and chemical tests to understand how the materials degrade over time.

Daniel Fonseca launched his career as a chemical technical professional at United Chemical Technologies in Bristol, PA. There, he developed and published a procedure to extract and analyze dyes from fish tissue to help a client in the textile industry determine whether the company’s dyes were impacting fish. Taking charge of a project and interacting with customers aren’t necessarily part of the job description for chemical technical professionals, says Fonseca. But his company was small, so he wore many hats requiring different levels of expertise. Fonseca later moved to Dow Coating Materials in Collegeville, PA, where, until a recent promotion, he helped analyze and develop new products for the paper coatings industry.

On the job

When Fonseca started as a chemical technical professional at Dow, a typical week involved receiving instructions from a project leader, setting up his workspace, running all of the tests he was directed to do, and then analyzing the data to deliver to the project leader at the end of the week.

“There is a lot of routine work,” says McCulley. “If there is something that is off track, that’s when they need to take it up to a senior chemist.” Though she notes that some more experienced chemical technical professionals may troubleshoot themselves.

Chemists with PhDs typically lead Perry’s projects at NIST. But Perry plays a key role—prepping samples and running analyses on sophisticated equipment. Some of this equipment she learned to use in school, but much of her training happened on the job.

Success as a chemical technical professional requires a high level of organization, says Caitlin Ewald, a fourth-year industrial chemistry major at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, MI, who spent the summer of 2021 interning in a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant in Allegan, MI. Ewald worked in quality control testing of ibuprofen, following a detailed lab protocol much like she would in a chemistry lab at school. “Time management is huge,” she says. “Record keeping, being able to take good notes.”

Chemical technical professionals must also be “extraordinarily passionate about what they pursue,” says Martino. “They have to be willing to get satisfaction out of tasks that may be repetitive.”

Perry, like McCulley, finds much of her passion in the instrumentation itself. “I’ve always considered NIST to be a playground for scientists,” she says. “We usually have the equipment, but if we don’t, we build it.”

Fonseca feels a sense of satisfaction knowing that his work as a chemical technical professional has resulted in products that many people use in their daily lives—from cereal boxes to disposable coffee cups.

And despite the routine nature of the work, a good chemical technical professional must also be ready for surprises. “You might have a rush sample coming in. You may have an instrument that is down,” says McCulley. “You have to troubleshoot some of those. That can be a very fun aspect.”

Chemical technical professional roles are not well suited to every chemist. Ewald ultimately decided to pursue graduate school. Although she enjoyed her internship, the work was more repetitive than she’d like.

But the oftentimes predictable nature of the job is what appeals to industrial chemistry technology major Breanna Kociba, also a fourth-year student at Ferris State University. “I’m a planner,” she says. “So the fact that I would come in and know exactly what was going to be done that day, it puts me at ease.”

Kociba took a course that mimics an 8-hour workday for a chemical technical professional. At the end of each day, she felt a sense of accomplishment. “Wow, I just made that,” she recalls thinking. “You feel like you belong somewhere, that your presence matters.”

Getting started and advancing

If you want to launch your own career as a chemical technical professional, Martino suggests looking for internships and undergraduate research experiences, which can give you an edge when entering the job market. If you’re at a community college without access to research labs, he recommends reaching out to your chemistry instructors to share your career goals. They may be doing research in conjunction with research universities or have connections to industry.

When applying, you’ll want to demonstrate how your education, work experiences, and strengths line up with particular job openings. “I want somebody who demonstrates attention to detail,” says Jim Egan, vice president of research and development at LaMotte, a Chestertown, MD-based company that produces water quality testing equipment. “Somebody who has lab skills, decent math skills, and is adept with computers.”

Historically, an associate’s degree was often a minimum requirement. The field is becoming more competitive, but there are still opportunities for associate’s degree holders. LaMotte hires both two- and four-year degree holders for chemical technical professional jobs, says Maria Coakley, vice president of human resources at LaMotte.

Perry now has a BS in chemistry, but she landed her first job as a chemical technical professional at the FHA after earning an associate’s degree. “No matter what field you are in, don’t let the degree keep you from at least trying,” says Perry. “It really helps when you network and you learn communication skills.”

Once you land your job as a chemical technical professional, you may choose to stick within the role that you were hired to perform. But if you want more responsibilities or leadership experiences, some extra effort could get you there.

Perry, Fonseca, and McCulley all advanced by taking on challenges that go beyond their defined roles. “In my job description, I don’t have to write papers,” says Perry. “It’s just something that I enjoy doing and I’m capable of doing.” Perry is also passionate about making sure that underrepresented populations are aware of job possibilities in STEM. She mentors interns and regularly reaches out to students at historically Black colleges and universities to spread the word about opportunities at NIST. Because of her passion and initiative, she is now transitioning to a new role in the academic affairs office where she’ll run some of NIST’s internship programs.

Fonseca taught himself statistical software, ran extra tests whenever analyses looked off, and regularly communicated with leadership that he wanted more responsibility. “Those kinds of initiatives helped me in my career to get me to where I am now,” says Fonseca, who recently transitioned to a new role as a lead technical service and development chemist.

To advance to leadership positions at some companies, you may need an advanced degree, says Martino. “You may want to consider going back for more education if that is something that you really want to pursue.” Some employers may even cover tuition costs.

McCulley earned her master’s degree to stay competitive but opted not to pursue a PhD. “There are some companies that the PhD is a requirement for upper management positions,” she says. “But there are a lot of companies that look at the skill set that a person has, the communication, networking, teamwork.”

Whatever your degree level and career stage, CTA is there for you, says McCulley. The committee keeps chemical technical professionals up-to-date on job and professional development opportunities through LinkedIn and Twitter pages, as well as through webinars.

And if you’re unsure whether to pursue this career direction in the first place, you could reach out to CTA members or ACS career consultants with questions. You could also take advantage of the ACS Career Pathways program, says Martino.

If you already know that you’re ready to get to work as a chemical technical professional, opportunities are out there. When asked what advice he has for young chemists interested in chemical technical professional roles, Egan says, “Come apply. We have openings.”